- Home

- M. K. Hume

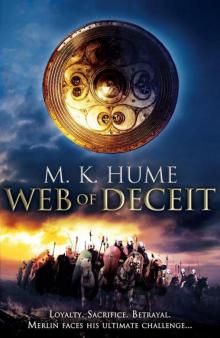

Prophecy: Web of Deceit (Prophecy 3) Page 13

Prophecy: Web of Deceit (Prophecy 3) Read online

Page 13

The prince had a mixed reputation, so Ambrosius was curious to see if the man matched the stories that filtered down from the north. Luka refused to use his father’s nomen, or even his given name, Llywelyn, being consumed by a fierce determination to win his own fame. Aspiring to the throne of the Brigante tribe was insufficient for him, for he rightly dismissed his eventual inheritance as an accident of birth. Ambrosius approved of such pride, but he was concerned and intrigued by Luka’s reputation for hot temper, excess and wild, elemental charm, for such character flaws were dangerous in an ally.

I’ll know soon enough, Ambrosius thought, as he exchanged glances with his brother. At least Uther has been less grumpy of late, although I have missed the company of the healer. The young man has the power to soothe, and his brain is sharper than Uther’s blade – and that’s saying something. It’s a pity that Uther is jealous of anyone who stands with me as an intellectual equal.

Just as Uther was becoming restive and angry at the delay in their visitor’s arrival, the ornate doors to the hall were opened with a flourish and Prince Luka entered, flanked by his personal guard, who had surrendered their weapons in the antechamber. Although the newcomers were unarmed, they still looked hard, dangerous and savage – especially the prince.

‘I welcome you, Luka of the Brigante tribe. I have heard whispers of trouble in the north and I hope you will inform me of any danger to my lands. I am pleased that, at last, the Brigante, the Atrebates and the other great tribes of the south can meet and exchange loyalties after many years of silence and distrust.’

As Ambrosius welcomed his visitor with his usual grace and warmth, his eyes narrowed on the hawk-sharp face that was lowered in a deep obeisance. Luka managed to appear compliant and independent at once, not only in the ready and deep bow he made so gracefully, but also in the quick measuring glance that examined the High King from head to toe as he rose to his feet. Ambrosius began to look for what lay beneath the superficial, blatantly ostentatious savagery of the young prince’s appearance.

‘Please be seated, Prince Luka, for there is no need to stand on ceremony on this day. Uther – a chair for our guest.’

This simple request established the notion in the minds of witnesses in the audience chamber that Uther and Luka were equal in standing at Ambrosius’s court. What Uther thought of this situation was impossible to guess. His face unreadable, he nodded curtly at one of the young men in his train.

Prince Luka accepted the simple stool brought forward by the nervous servant, and then visibly relaxed. Ambrosius registered the amber-brown eyes that gazed at him with candour and an unsettling assessment. Of little more than average height, Luka made up for his lack of inches with a muscular, slender form and quick-moving hands that were as animated as Ambrosius’s own. The prince’s fingers were long, scarred by sword practice and many years on horseback, and Ambrosius could see them caressing a woman with equal skill. Under the High King’s regard, Luka fiddled with his intricately worked electrum torc, so Ambrosius became conscious of the prince’s love of display. A brace of arm-rings of massy gold, as well as several large, barbaric and vivid finger-rings decked Luka’s body with easy panache.

‘Lord, the Picts attacked from beyond Hadrian’s Wall in strength. Summer was well advanced, so they caught us by surprise. Far beyond the Vallum Antonini, they had obviously planned their invasion secretly and carefully, depending on speed and surprise to counteract the lateness of the season. After carving through the Otadini and the Selgovae tribes, they drove deeply into our lands before we could muster the levies, so many warriors died to blunt their advance.’

‘An unusual and subtle strategy for Picts to use,’ Ambrosius murmured. ‘Someone in the north has been thinking hard, knowing our eyes have turned towards the east and the Saxons with the approach of summer.’

‘Aye, lord,’ Luka agreed. ‘We had fortified the fortresses of Lavatrae, Bravoniacum and Cataractonium, so we were outfoxed entirely when Talorc, the Pict king, attacked Luguvalium, then Brocavum, before driving his army through the mountains towards Olicana and access to the green lands of the south. But their speed was their undoing, as well as the reason for their initial success. We have long used the old Roman fortresses of Verterae and Petrianae, and Talorc bypassed these two citadels without leaving a force behind that could keep our troops pinned down.’

‘A mistake.’ Uther snickered from behind Ambrosius. ‘It’s stupid to leave your rear unguarded. I wish I’d been there to enjoy the fun.’

‘I doubt it was fun, brother. I can imagine that the loss of life must have been frightful,’ Ambrosius chided gently, and he saw the sudden furrow of distaste between the Brigante’s eyes. So Luka was more than just a fighting animal, the High King thought.

‘The men of all the fortresses marched to intercept the Picts, while leaving only token forces to guard the eastern marches. My father gambled on a single, decisive battle that would finish the Picts for generations – or destroy us.’

‘Tell us, Luka,’ Uther murmured eagerly, for he was engrossed in the Brigante’s story.

‘We drove north through Olicana and made a forced march towards a river valley that could impede the Pict advance. Mountains ringed the valley, and the wild sea cliffs lay to the west, so we trusted our brothers from the fortresses to guard our backs. We met the Picts on the banks of the river, and the clash of men on horseback shuddered through the two armies. Our levies ground together like stone on stone so that no side had an advantage and the battle continued long and fierce. The Blue Men gave no quarter and fought until they perished.

‘Then, just as I was beginning to despair of breaking the Pictish ranks, the troops of Verterae and Lavatrae poured out of the hills, both afoot and on horseback. Their impetus, as they charged down the long hill to engage the enemy, cut a huge hole in the rear of the Pict army and gave us heart to continue the struggle. Step by bloody step, we gained ground and managed to pin the Picts into a deadly circle.’

‘Did Talorc surrender and parlay for terms, or retreat like a sensible man?’ Ambrosius asked, easily able to visualise the blood-churned mud and the heaped corpses of a desperate struggle to survive the conflict.

‘We offered them terms, my lord. I know the Brigante tribe has a reputation for ferocity, but we are honourable men. Once we knew the battle was won, my father called a truce and sent me to offer them a chance of surrender without humiliation, but Talorc spat in my face. I had to use all my weapons’ skill to escape unscathed, for the Picts were prepared to break the truce. Once I rejoined our force, my father ordered the net closed and we slew their men until our arms were almost too heavy to lift our swords.’

‘Terrible,’ Ambrosius murmured, for he regretted the loss of so many warriors.

‘Aye, it was terrible. But our losses were light compared with those inflicted on the enemy. Many widows beyond the two walls will wail in sorrow when their men come home no more. And they will sing songs of the death of Talorc for generations, for he refused to surrender and died where he stood. We despise the Picts out of long habit, but I would be blind if I didn’t admire Talorc’s fierce courage in the face of certain death. Only when the king had perished did the will of the Picts break, and they started to run. We allowed them to pass back into the north, but only a few hundred men will return out of the thousands who marched into Brigante lands only weeks before.’

‘I take it that you captured the baggage train,’ Uther interrupted, eager to determine the value of the Pictish war chests.

‘Aye. As the emissary for my father, Lord King Ambrosius, I beg you to accept one fifth of all that was taken from the dead and the dying. What remains will succour our widows and orphans, as well as fortify our borders, for we believe the Saxons will consider the aftermath of this conflict with the Picts to be an opportune time to attack us.’

Luka gestured towards one of his guard, who struck the closed doors with his fist. A group of warriors entered, bowed under the weight of the wooden ch

ests, bound with iron bands, that they laid at Ambrosius’s feet. One of the warriors opened the lids and exposed piles of looted valuables that filled the chests to the brims. Under the ruddy light of the torches, the gold, silver and bronze that had been stripped from the dead seemed to have been washed with the sheen of blood.

‘I have heard that you took hostages as well,’ Uther cut in over Ambrosius’s courteous thanks, causing the High King to dart an admonishing glance in his direction.

‘Behold the household of Talorc, king of the Picts,’ Luka cried in a ringing voice as a group of women was herded into the audience chamber. They entered on naked feet, for they were chained and humbled, so the links of their shackles rang dully as they swayed into the circle of lamplight.

The Pict women were quite short, but they were proud and very shapely. They wore their tattoos with pride and stared at their new masters with palpable scorn. Even as Luka introduced the Pict queen, an older woman whose hair was liberally streaked with grey, Ambrosius found his eyes drawn to a red-haired woman who was unmistakably Celt in appearance. Her green eyes were insolent and angry, and she scorned to hide her partial nakedness with her long tattooed hands.

The woman’s lissome body and the endearing freckles across her nose, forearms and breasts impressed Ambrosius. Even the sharp enmity in her eyes caused his loins to tighten painfully. Ambrosius had always trodden carefully around the fairer sex, for he had a healthy respect for the reputed female penchant for slyness and manipulation. Even the need for an heir was not overly pressing, as Uther could step into his shoes should accident, assassination or death in battle send the High King prematurely to the River Styx. Not that Ambrosius planned to pay the Ferryman early: far from it. The king nurtured grandiose plans for the future of the people of the west, ambitions that would take time to bring to fruition. Unlike his brother, he recognised that there were many Saxon thanes of character and pragmatism who might well enter into alliances under some form of truce. Further, he believed that little actually separated Saxon and Celt but blind prejudice, for even their gods and customs were similar. With patience, Ambrosius believed he could blunt the violence of the past and build a lasting accord with Saxons of goodwill.

Even as his mind ranged over the many possibilities open to him, he continued to stare at the Celtic woman intently. Finally Luka interrupted his liege’s abstracted concentration.

‘What do you require us to do with the captives, my king?’

‘They may stay or go as their hearts dictate. I’ll not turn noblewomen into slaves. They are free to find new husbands or masters if they wish to remain in Venta Belgarum. Let each woman who chooses to leave be given a horse and enough supplies to last for a week. She may then return to her home as best she may.’

The noblewomen whispered together with a sound like wind soughing through dried grasses. Their faces were closed and blank and their bodies were rigid with revulsion.

‘Then we will depart this heathen place,’ the Pict queen decided in a voice that was deep, resonant and charged with sexual promise, although she must have been past the age of childbearing. ‘The mountains of the north wind call to us and my husband’s shade demands to be set free of the chains of this world.’

The other women swayed and nodded, so that Ambrosius imagined that he gazed at flower women, heather women, blue with their tattoos and the midnight blackness of their manes.

‘My lord,’ Luka protested. ‘These women are from noble families who will be prepared to pay a ransom for their safe return. You cast away gold that would enrich your war coffers.’

‘I don’t make war against females,’ Ambrosius snapped. ‘And who is that Celtic woman? She’s obviously not a Pict, so she has no business being chained.’

‘She damned well acted like a Pict when she bit me,’ Luka responded roughly, still smarting from the king’s rebuff. ‘She was married to one of the lordlings. But don’t ask me which one, as I can’t pronounce their heathen names.’

‘Stand forth, woman. I know you understand me. Who are you, and what are your antecedents?’

Ambrosius’s tone left no room for disobedience, so the Celt stepped to the front of the cluster of women with her chin lifted in pride. Her steps were graceful and turned her slightest movement into a promise.

‘My husband’s name was Garnaid, lord of the area north of what the Romans called Camelon, beyond the Vallum Antonini. The Romans ceded us those lands, believing us to be too barbaric to dwell on softer, more civilised soil. And you could not dislodge us, no matter how hard your ancestors tried. But some of us still dwell in the lands of the Selgovae and Damnonii, in an uneasy truce with the tribal kings and suffering much poverty. Some Otadini tribesmen hunt us like vermin, yet you consider them to be noble.’

Her voice was light and lilting, although she spoke Celt with a limping accent, as if she had been stolen from her people a long time ago.

‘I repeat, woman, what is your name and where do you come from?’

‘I am Bridei, once called Andrewina Ruadh when I lived in my father’s house near Rerigonius Sinus. I grew up within a stone’s throw of the wild sea, a daughter of the Novantae tribe. When I was ten years old, I was stolen, or rescued, by a raiding party from beyond the northern wall, and became a replacement for a murdered daughter. In the north, I learned what it is to be free and no chattel of ambitious men. There, I married as I chose and bore sons, so I thank you for permitting me to return to my bairns.’

‘But you’re not a Pict!’ Ambrosius exclaimed, affronted that a well-born female would prefer the travails of the icy north.

‘And you’re a Roman, Ambrosius Imperator, and not a true Celt in blood. As such, you belong in Rome, don’t you? No? Like you, I choose to be where my heart dictates. I am now a Pict.’

‘By birth and bloodline, you are Celt until it is established whether your kin will take you back. If none is found alive, or your family should reject you, then you may go where you choose. In the meantime, you may serve in my kitchens.’

Bridei flashed Ambrosius a malicious glance that could blight the immature ears of wheat. The High King smiled a little at her defiance, although Uther clenched his fists at her arrogance and decided that this woman should meet with an unfortunate accident.

‘I’ll not be a servant to my people’s enemies. You’ll have to chain me.’

‘Of course, my lady,’ Ambrosius agreed equably. ‘If such is your desire.’

Then, as the women were ushered out of his hall, the High King turned his back on her to talk to Luka and Uther. Bridei was led away in chains. Her heart ached for her sons, but her pride did not permit her to weep.

Myrddion lay curled in his cloak in a thick nest of dried leaves outside Tomen-y-mur as he waited to ride into that benighted town. He had ridden far, visiting the towns of Glevum, Venta Silurum, Isca, Nidum and Caer Fyrddin. At first, he had been unsure of ever finding eyes and ears for Ambrosius, but he had been mistaken. Years of war had taken their toll on the British people, and kings and commoners alike gave thanks for the night that Vortigern had perished at Dinas Emrys. They were vocal in their praise of peace, at least in his hearing, and at Isca Myrddion even heard the tale of Vortigern’s burning, told with much elaboration, by an old soldier who claimed to have been at the fortress when the old monster died. Initially, Myrddion had wanted to hide in embarrassment, but he covered his hair with the cowl of his cloak, sat quietly at the back of the inn and listened in amazement as the unlikely tale unfolded.

‘It was a lucky day when the gods took pity on us,’ the warrior explained to a rapt audience. ‘We’d suffered sorely from the tyrant’s cruelty and it seemed we’d be killing each other for years. Civil war was like to turn Cymru into a wasteland full of weeping widows and starving children. Let’s face it, what harm does Ambrosius do to us? We send our share of tribute and the levies, and we’re left to live our lives as we want. But under Vortigern’s iron fist? I remember it well, mind, so I’m glad the bastard’s saf

ely dead.’

‘But how did it happen, Ewen? I’m told he died in a storm,’ a plump-faced farmer asked, pouring ale from a brimming pottery jug into a mug clutched in Ewen’s gnarled fist. Gratified with the response, Ewen took a deep quaff of the ale and brushed his grey moustaches clean. He preened visibly.

‘I tell you that the good god Bran sent the lightning that struck Vortigern. It burned him up in seconds. Ugh! What he looked like afterwards! We were sick when we tried to move the king’s corpse. He fell apart like over-cooked meat.’

Ewen continued to elaborate on his grisly tale to the groans, cheers or grimaces of the crowd, but Myrddion had heard enough. Yet the flashy lie was of use, for it ensured that Myrddion’s mentor, Eddius, remained safe, despite lighting the fire that caused the death of King Vortigern. Nor did Myrddion have the heart to blame Eddius for his sin of regicide. Eddius’s wife, Olwyn, Myrddion’s grandmother, had been killed by the king’s own hand and her blood had cried out for vengeance from beyond the grave.

‘A pretty fallacy,’ he whispered.

The man next to him glanced up at Myrddion sharply and then, surprised, narrowed his eyes in recognition.

‘I know you, master.’ The man spoke softly and deferentially, for he remembered the sunburst ruby on Myrddion’s index finger. ‘You were the healer at Tomen-y-mur. You’re the Demon Seed.’

‘Were you there, my friend?’ Myrddion sighed. He had already found some men and women who were eager to serve him because he had saved their lives after one of the many battles fought during Vortigern’s time. Their admiration made them eager to repay him, and Myrddion sometimes believed he was taking advantage of their gratitude.

The Emperor's Blood (e-novella)

The Emperor's Blood (e-novella) King Arthur: The Bloody Cup: Book Three

King Arthur: The Bloody Cup: Book Three The Blood of Kings: Tintagel Book I

The Blood of Kings: Tintagel Book I King Arthur: Dragon's Child: Book One (King Arthur Trilogy 1)

King Arthur: Dragon's Child: Book One (King Arthur Trilogy 1) King Arthur: Warrior of the West: Book Two

King Arthur: Warrior of the West: Book Two The Storm Lord

The Storm Lord The Poisoned Throne: Tintagel Book II

The Poisoned Throne: Tintagel Book II![M. K. Hume [King Arthur Trilogy 04] The Last Dragon Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/m_k_hume_king_arthur_trilogy_04_the_last_dragon_preview.jpg) M. K. Hume [King Arthur Trilogy 04] The Last Dragon

M. K. Hume [King Arthur Trilogy 04] The Last Dragon Prophecy: Death of an Empire: Book Two (Prophecy Trilogy)

Prophecy: Death of an Empire: Book Two (Prophecy Trilogy) Prophecy: Web of Deceit (Prophecy 3)

Prophecy: Web of Deceit (Prophecy 3)